Khasi Traditional Food – Health in Tradition

When it comes to food, people nowadays are spoilt for choice. There’s food every way one looks. The streets are full of them, suiting every palate and pocket.

But, are they healthy? Possibly. Possibly not.

There is one undoubtedly healthy option: traditional fare of the tribes that has stood the test of time, still using age-old cooking methods.

Appearance, taste and texture look the same as when your grandmother first dished them out to you. Unchanged through the years. Made from ancient grains, original, non-GMO, traditionally grown, and unique.

Here we’ll talk about food prepared by the Khasis, the largest tribe in Meghalaya. Their original food has been the same for years, if not generations - pure, simple and wholesome.

We thought, wouldn’t it be nice to meet the very people who give us these delicacies to find out who they are, where and how they make the food, their modus operandi, and their business strategy.

We bring you the story of our trip so you learn some of the Khasi tribe food.

Find out what is unique about Meghalaya and the potential of the land. Download ebook.

People Behind Khasi Traditional Food

Soon enough we landed in Kong Elisabeth Pasi’s house, in a little corner of Shillong’s Mawlai locality. Her ‘kitchen’ is a one-room affair, in one corner of their property, separate from the main house.

Wood-smoke greeted us when we arrived by 9 a.m. Business began an hour earlier. In fact, they start their mise-en-place the previous evening by 4 p.m.

Kong Elisabeth, in her fifties, along with her helpers – husband, children, and brother – had no time to waste. Streams of customers kept pouring in, and they had to complete their daily firm order supplies too. By 12 noon all she makes is sold!

“There are even customers from abroad”, Kong says. Now that’s indigenous going global!

Elisabeth’s story

Originally from Jaintia Hills, Kong Elisabeth tells us that she inherited her mother’s legacy 26 years ago. Before that, her mother did the same business for 45 years. That totals up to 71 years of gastronomic service to myriads of people in Shillong and elsewhere!We cook in the authentic, traditional way,’ Kong tells us, ‘as my mother taught me.’There are still customers from way back when her mother was alive. They stick on because of authenticity.

We use only traditionally grown rice, never mixing with inferior quality grains’ Kong affirms, ‘authenticity suffers otherwise.’

Khaw (Khasi for Rice), The Main Ingredient

They procure ‘Khaw’ (pronounced ‘khao’), directly from the growers to ensure purity. Three types of khaw are used in the preparations:- Khaw Mynri for Pu-maloi, Putharo and Pu-doh

- Khaw Pnah or Khaw Biruin (khasi sticky rice) for the Ja-shulia (steamed sticky rice preparation)

- Khaw Manipur (Manipur rice) for Pu-khlein and Pu-sla

We saw only white rice. ’Customers’ preference’ explains Kong Elisabeth, ‘but when orders come, we use the more expensive red rice too.’

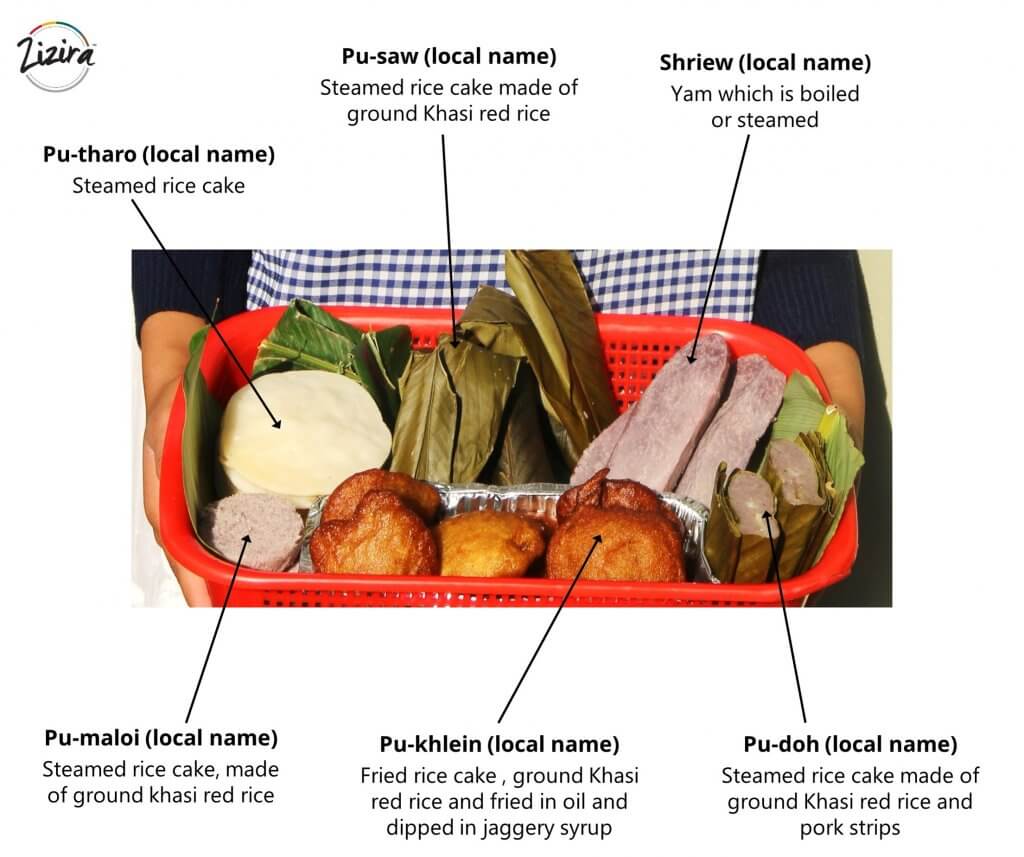

Khasi Traditional Food - Quaint Names, Quaint Shapes, Same Goodness

Let's look at the very common Khasi tribe food loved by the locals.

The names of these Khasi traditional foods are peculiar, sometimes unpronounceable: Pumaloi, Putharo, Pukhlein, Pu-sla, Pu-doh, Ja-shulia…and many others.

‘Pu’ is short for ‘kpu’ meaning cake, rice-cake actually.

Suffixes describe the type of cake:

Pu-sla literally means cake steamed in a ‘sla’ or leaf.

Pu-doh is stuffed with ‘doh’ or meat,

and Pu-khlein is fried in oil (khlein).

These foods that the Khasi tribe have been using for generations have no additives, are healthy and can be eaten without fear of upset tummies. They fill thoroughly, satisfying one like no other food can.

Made of different varieties of rice, they are either steamed or baked. Oil-free and salt-free they go easy on the tummy while they delight the palate.

Admittedly one has to first acquire a taste, as they are as bland as ever. Accompanied with meats, vegetables, stews, chutneys, they make delightful combos.

Khasi Traditional Food?- Easy to Prepare?

No, a tedious process, Kong tells us. Rice has to be thoroughly sorted and sifted and cleaned of any foreign bodies like stones, seeds, sticks etc. Then it is put into a large wooden ‘thlong’ (mortar) and with a wooden ‘synrei’ (pestle) it is pounded into flour or powder.

Time to time they fine-sieve the flour, to segregate the larger grains from powdered ones, repeating the pounding process till all grains are finely and evenly powdered. So, what is used is hand-pound rice powder!

Rice powder is made into a batter to be steamed, baked, or fried, as desired.

For Putharo – flat rice cakes- the batter is ladled, singly, on to an earthen pan called ‘sarao’, a clay pan specially obtained from Ialong in Jaintia Hills District.

Throughout the baking process, the fire is controlled for the right amount of heat.

Steaming is done by

- Placing a pan with holes at the bottom over another pan of boiling water.

- Boiling water in a steaming container with a hole on the lid.

Pumaloi batter is poured into a mould, covered with cloth and then inverted over the steaming container.

Pu-doh (batter with meat stuffing)

and Pu-sla (batter mixed with jaggery) are wrapped in La-met leaf (Phrynium placentarium ) and steamed in a pan.

Pu-khlein is also mixed with jaggery and fried in refined oil.

Jashulia (steamed sticky rice) preparation demands several washings of the rice before steaming.

In all preparations, no direct boiling is done, except for Pu-khlein which is fried.

These folk sticks to tradition, modern food joints notwithstanding. They make food that’s pure, natural, safe and, above all, nutritious and healthy.

The ingredients come from the good earth, untainted by technology. Their know-how comes from their ancestors, tested by time, consumed through centuries without ill effects.

This is what Zizira constantly endeavours to explore, joining hands to preserve tradition and pass on to the world the goodness of native foods and grains.